The Bloody Guts Inside Our Games

Making games is a messy business. From a lone idea, the journey they take to reach our hands is fraught with blood, sweat and a whole lot of tears.

The games industry is a business. There is no getting around it. Money is a crucial component of its operation, whether we're talking AAA blockbusters or home-brewed indie titles. Even games made purely as a hobby need to be supplemented by a tertiary income to feed, clothe and shelter the people sacrificing their precious time to it. The substantial costs of the big, slickly-produced experiences that many gamers have come to expect are simply too steep to be funded out-of-pocket by all but the richest philanthropists.

That is why many indie games adopt two dimensions instead of three, utilise simpler art styles and procedural asset creation, and opt for dialogue text over professional voice acting. It's why the race to the 99c price point on the App Store has spawned countless clones and innumerable games relying on murky microtransactions just to make back their production costs. It's why the Kickstarter darling Broken Age had to scrounge up additional investment from external sources despite skyrocketing past its initial funding goal. The fact that games are a source of entertainment often blinds gamers to the fact that they are products too, and just like cars, concords and computers, what you see on the outside bears little resemblance to what's under the hood.

Recently, Double Fine, the developer of the aforementioned Broken Age, released the documentary series chronicling the point-and-click adventure game's development for everyone to watch on YouTube. Showcasing the highs and the lows that the game went through over the course of the three year development, the series doesn't paint the prettiest picture of a game's life cycle. That, of course, was the impetus behind filming the whole thing. Double Fine wanted to show people just how complicated making a game was, especially from the business side of things. With its project being the first big, crowdfunded game, it wanted to maintain complete transparency in order to ensure backers knew what their money was being used for.

The series definitely achieves that.

Budget meetings, resource allocation, deadline debates, 12-hour crunch days: there are no punches pulled when it comes to exploring the ugly side of making games. This unprecedented coverage exposes many truths the games industry tends to downplay in order to maintain a façade of glamour and mystique. There's nothing necessarily wrong with that - for the consumer, entertainment is primarily about the end product, not the process that created it - but it's refreshing to get an unapologetically open look at the trials and travails involved in crafting the experiences we so cherish.

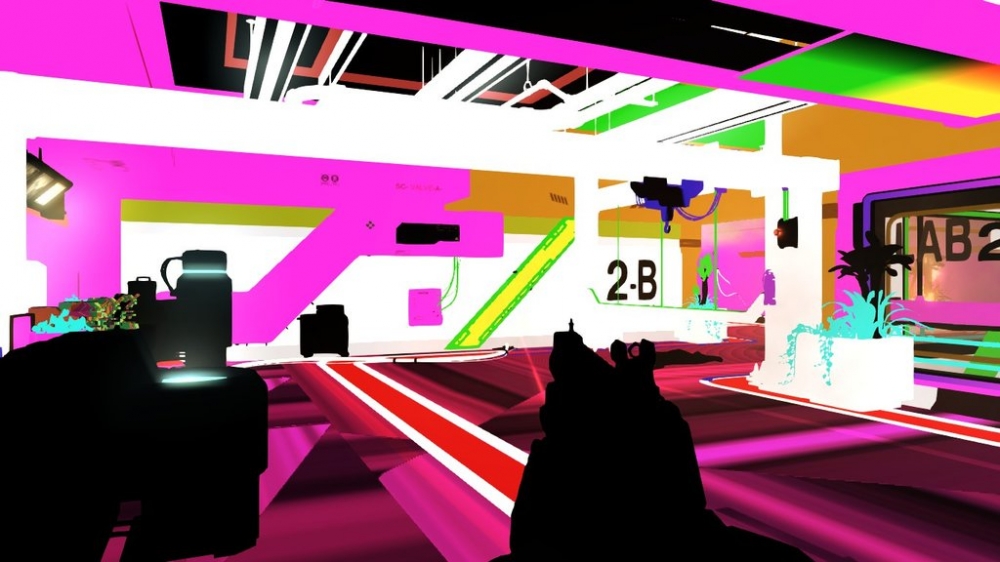

As the subject of scrutiny, Broken Age illustrates well the general misconceptions game development is saddled with. Being a 2D, slow-paced, point-and-click adventure game, it lacks the enormous photo-realistic 3D spaces of an Assassin's Creed, or the explosive chaos of a Grand Theft Auto. At first glance, it seems so simplistic - albeit pretty - that it's not hard to fall into the trap of extending those surface-level impressions to the entire game. Surely it can't be that difficult to make puppet-like characters move across flat planes. All they ever have to do is walk and talk in front of alternating backgrounds. It's a Broadway production in a digital mask!

The thing is, a show on Broadway isn't cheap. Ignoring the operating costs, production is often in the region of $10 million (source). That's for something that unfolds in a couple of hours across a handful of static scenes, with a cast of characters many of whom get paid very little - passion is their primary motivation. Certainly the physical construction of costumes and sets is substantially more expensive than equivalent digital replication, but due to the grander scope, length, and interactivity of a game like Broken Age, a comparison is not invalid. Voice acting, for instance, is almost directly comparable; Jack Black, Elijah Wood, Wil Wheaton and Jennifer Hale are all big names that lend their talents to Broken Age, and they don't come cheap.

Also Read: A Post-Mortem of Broken Age

Considering the similarities, it seems a little unfair that the phrase 'Broadway show' is most often associated with finery, luxury and decadence, while "adventure games" are typically perceived as being simple and disposable. There are just as many, if not more, costs to consider when developing an adventure game than there are in producing a Broadway show.

Let's take art, for example, as one of the more obvious expenses. The visual style is the first thing that the player sees, and it colours their experience throughout the entirety of the game. In adventure games, because the scenery is often static and flat with limited objects of interaction, the temptation to assume its creation is as easy as painting a pretty picture and slapping a couple of characters over the top of it is understandable. After all, that's essentially what the player sees. In actuality, though, there's a whole lot more to it. In a game as dense as Broken Age, every time a character interacts with an item, another character, or the environment, that's a new animation that needs to be built, not to mention a new line of dialogue to be written and recorded.

The scenes aren't actually static, either. Doors open and close - a couple more animations right there. Non-player characters move and talk even while the player is doing nothing - that's more animation. The player character needs to move through the world in such a way that their limbs react to obstacles and elevation without clipping through solid objects, and the illusion of perception must maintain a sense of depth through the two dimensions. Heads and eyes need to organically focus on objects of interest - if characters were always looking dead ahead, conversations between them would be quite stiff and unnatural. Turning circles and movement speed need to balance realism with responsiveness - a headlong sprint across the screen might look ridiculous, but the player won't enjoy waiting for their character to clamber up a cloud-piercing ladder at a lifelike pace.

These are only a handful of the countless considerations relevant to character movement, which is itself just one small component of the artistic element of an adventure game. Extrapolate them out, and you start to get a clearer picture of the tremendous effort required to produce even the most basic of mechanics.

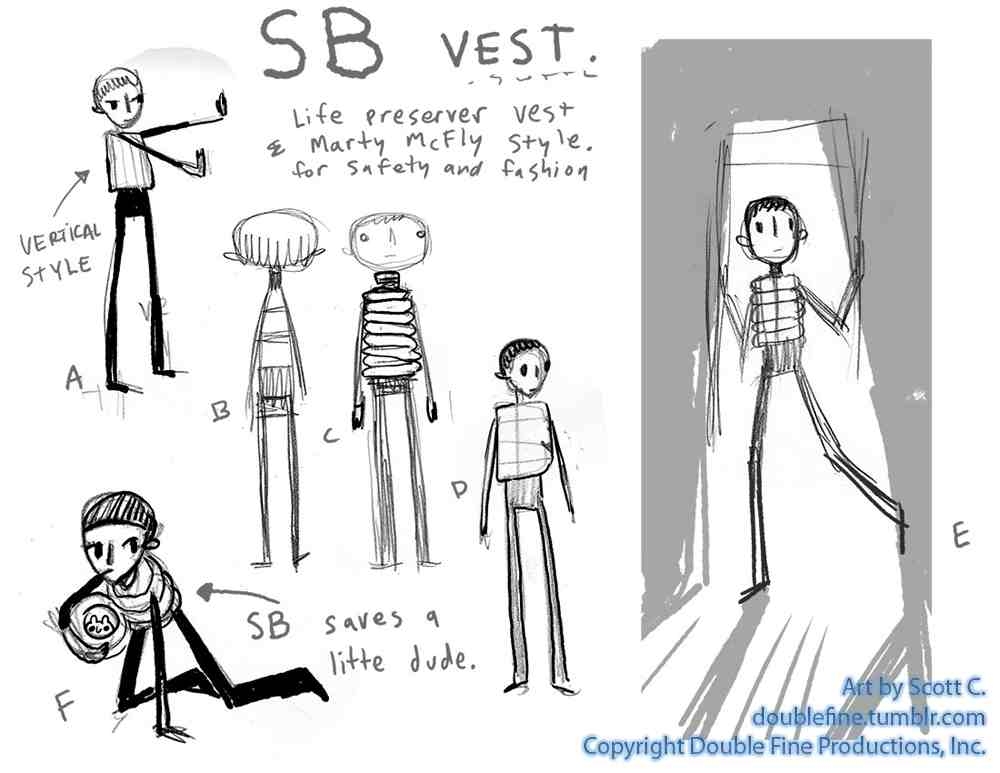

Continuing with the art example, a key concern of any game - especially one with as distinct and powerful a visual style as Broken Age - is maintaining a cohesive artistic motif throughout its many parts. This is not as simple as it might first sound. A unique art style is often born of the mind of a single, particularly creative individual. That is, essentially, the genesis of uniqueness. To have this individual single-handedly create every art asset required for a game of Broken Age's scope is wholly unfeasible - within any sort of reasonable time and money constraints, that is. So other artists must be brought in to divide the workload.

The problem now is ensuring the integrity of that distinct art style. The other artists will each have their own unique visual tone, and to have them not just simulate, but emulate the original artist's style is a tough ask. A decision has to be made: should the artist with the singular vision be responsible solely for ideas and concept sketches while leaving the actual implementation to others, or should a collaborative effort be attempted in the hopes that the spark of individuality isn't extinguished by the too-many-cooks conundrum? Both approaches come with trade-offs, and no matter how well they are executed, the result is unlikely to live up to the vision the designers and developers dreamed of.

Another interesting issue highlighted by the Broken Age documentary doesn't have much, if anything, to do with the actual development of the game. In crowdfunding campaigns, backer rewards are a crucial tool for incentivising avid fans to pledge more money to the development process. Offering t-shirts, posters, autographed photos and other physical goods attracts the collectors, but it adds considerable overhead in both time and money to the game's production. The more exclusive rewards like an invitation to have lunch with the developers or creative input in part of the game's design might not stretch the financial budget, but the time and logistics involved in fulfilling them mean many lost man hours.

Even the seemingly insignificant inclusion of a backer's name into the credits requires some effort, screening for offensive names and adjusting the text scroll speed and composing background music accordingly. Double Fine did not offer anything particularly flamboyant for Broken Age's various reward tiers, yet the initial deliverables immediately swallowed $400,000 from the campaign budget. That's a ninth of the total funds, siphoned away before development could even begin.

At the other end of the PR pipeline is the creation of marketing material. From artwork to trailers to playable demos - as rare as they are these days - it is not as quick and easy as just co-opting content from the game itself. Posters and screenshots need to tease the best elements of the game without spoiling them for players, something that is significantly harder than it may seem. Game assets must be cleaned up and edited for clarity, and given the fact that marketing runs parallel to development, anything shown must be certain to make it into the final game, lest complaints arise demanding to know why the gorgeous castle in the promotional posters can't be visited in the finished product.

Trailers are even more fickle. Since games often don't come together from a neat holistic perspective until late in development, marketable gameplay footage can be hard to come by. Instead, many trailers opt for pretty cinematics embodying the themes of the game, leaving the details to the viewer's imagination. Even those that do show in-game scenes are incredibly frugal with what they reveal. Scripted sequences and second-long snippets are all we see, because they are literally the only presentable elements that exist at that stage of development, and often only because they've been built specifically for the trailer. Another case of precious development time spent not actually making the game. Unfortunately, whether crowdfunded or traditionally published, games live or die on the strength of their marketing.

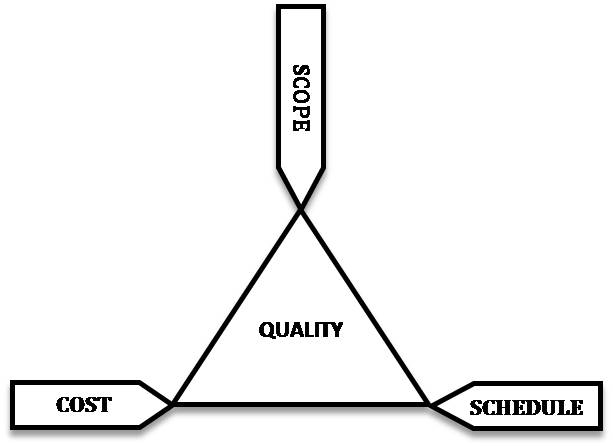

As in all business, games development involves trade-offs. There is no shortage of disparate conditions vying for satisfaction: prospective gains versus current expenditure, development time versus release deadline, perfection versus completion. The best solution is often not the one that makes everybody happy, but the one that leaves no one angry. This philosophy is readily apparent with regards to a game's scope. Early on in a game's life, in pitches to publishers, managers and the general public, developers typically sell a vision of the game that is huge, expansive and ambitious. A game that will forever change the landscape of the industry; that will establish itself as a tentpole title in the history of gaming.

More often than not, though, the final game will be a far cry from this early vision. Is this because the developers were con-artists trying to weasel money out of the trusting and gullible? Not likely. No, the enthusiastic men and women almost certainly believed fully in those early ideas and their ability to deliver on them. What they may not have been so wise to were the difficulties that inevitably cropped up during development. Budget cuts, personnel problems, technological hurdles, and other issues difficult to see from the starting line arise to throttle the magnitude of the original vision.

Features get cut under duress, the original dream clashing with the need to stay within budget and hit a promised release window. Graphics get "downgraded" from the quality of early trailers, not because the developer wants to cheat its fan-base, but because the only way it can hope to recoup production costs is by targeting the largest demographic possible, and that means ensuring the game can scale across numerous different tiers of hardware. When a promising element of a game's pitch doesn't make it into the final release, it's not because the developers are lazy or liars; it is because they are only human, and all humans are subject to the need for concessions. There is no deception here; no developer actually wants their game to be bad.

Consider a personal example of the fallibility of human planning. How many times have you organised an appointment, setting aside what you're sure is ample time to get ready and get to where you need to go, only for everything to go arse-up in the execution? I can recall numerous occasions where I underestimated the effect of peak-hour traffic, ignored the possibility of public transport delays, or just plain slept in through my alarm. These are unintentional errors made in areas of my life that I am intimately familiar with, yet my judgement still failed. Imagine having to plan and predict for something as big, complex and, by its very nature, uniquely unpredictable, as the development of a video game.

No matter how experienced a developer is, the sheer number of moving parts and uncontrollable variables means that forecasting the development process is about as accurate as predicting the weather on this day ten years from now - oh, there'll probably be some cloud, some sun, maybe a little wind…

The inevitable flaws of prediction were evidenced in Broken Age when Double Fine was forced to split the game into two halves, releasing the first act on its own in order to generate additional income to finance completion of the second act. Despite the unprecedented success of its Kickstarter, the developer still came afoul of the vision versus budget quandary. In its case, it was lucky; a crafty solution along with the support of fans ensured the scope of the game did not suffer. Most developers, though, don’t have this luxury, and their only option is to cut, cut, cut until they can squeeze their game into the ever-shrinking box that is their total budget. It's not a pleasant process. Nobody wants to neuter their creation. Tears and blood are spilled over the cutting room floor; the regret the developers feel is many times that of the disappointed consumer. I take pains to remember that when confronted by discrepancies between a pitch and a finished product.

Making a game is a monumental task. The amount of blood and sweat poured into one might not always shine through from the outside, but that doesn't mean it's not there all the same. The sheer magnitude of work involved is something worth keeping in mind the next time the urge to play armchair developer bubbles to the surface. Criticism and honest feedback are vital components of the industry, and they are a whole lot more valuable when they come from a considered perspective. Merely proclaiming. "this game sucks!' does little to encourage improvement in our nascent medium.

If you have any interest at all in the art of games development, I implore you to watch the Double Fine documentary on YouTube. It opened my eyes to many factors I had never given thought to, and bestowed on me a much greater appreciation for the games that I so love. One particularly poignant sentiment that stuck with me came from Tim Schafer, founder of Double Fine and the creative lead on Broken Age. With his characteristically incisive wit, he points out the incongruity between the expectation for a game to stick to a strict development and release schedule, and the absence of praise for doing so. No one ever says "wow, that game had a really reasonable protection time! I really appreciated its frugal use of its limited budget!"

We may not always want to know what goes into the sausage, but ignorance does not bestow bliss. It's important to remember: developers are people too.

Writer:

Matt Sayer